We were asked a lot of questions about eagle tracking during After the Fledge. D1, D14, Four, and D24 and D25 are part of a study by biologist Brett Mandernack from Eagle Valley: the first and, to date, most extensive tracking study in of free-living eagles in the Upper Midwest. Brett’s transmitter and field research have collected a wealth of data about the migratory, wintering, and summering behavior of bald eagles.

The most commonly asked question involved the PTT antennae located on the eagles’ backs. Could they be removed or shortened? How do the transmitters work and why are they the length they are? This blog attempts to answer those questions. Warning: it requires a fair amount of reading and has a long resource list at the end!

Can you get rid of the antenna?

We cannot. An antenna is needed to transmit data from the PTTs worn by our eagles. The PTT and GPS units from Geo-Trak Inc. collect and encode data about location, heading, speed, time, activity, and transmitter and battery performance. The encoded data is supplied as energy to the antenna, which radiates it as UHF radio waves to the Argos satellite network orbiting 528 miles (850 kilometers) over our heads. From there, ground stations receive real time data from the satellites and retransmit it to regional processing centers where we can access it. No antenna = no data.

Why can’t the antenna be smaller? Couldn’t it be part of their leg bands?

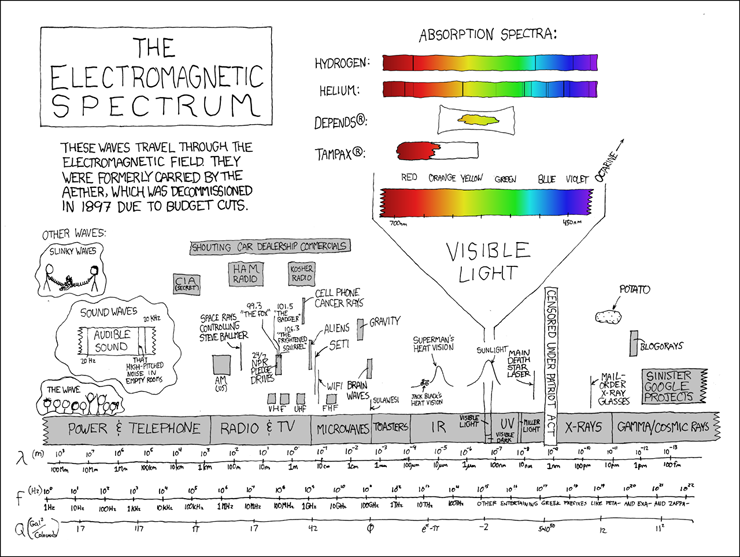

Let’s start with a quick primer. When we talk about radio waves, we are really talking about a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum - the range of all types of electromagnetic radiation (EMR). EMR is classified by wavelength into radio wave, microwave, terahertz (or sub-millimeter) radiation, infrared, the visible region that we perceive as light, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays.

Our transmitters are talking from eagles on the ground to satellites in space using radio waves with a frequency of 401.664 MHz. As the chart above shows, the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength. The shorter the wavelength, the smaller the antenna. So if a higher frequency means a smaller antenna, why aren’t we broadcasting at, say, 30GHz – the top end of the radio spectrum? An organization called the

International Telecommunication Union coordinates the shared global use of the radio spectrum, which includes assigning radio frequency allocations for space communication. 399.9 - 403 MHz is the band that ITU has allocated for navigation, positioning, time and frequency standard, mobile communication, and meteorological satellites. Geo-Trak’s satellite tracking products use the Argos satellite network, which transmits and receives data at 401.650 MHz (± 30 kHz). Argos is using the highest frequency available to them.

So why does frequency impact antenna size? The wavelength of a frequency is the distance an electromagnetic wave travels to complete one cycle. As the image at right shows, a 401.664 MegaHertz signal (a signal that oscillates, or moves through a complete cycle 401.664 million times in one second) has a full wave length of 29.38 inches, a half wave length of 14.69 inches, and a quarter wave of 7.34 inches.

For the antenna to radiate properly, it needs to match either the full wave or one of its major harmonics. Therefore, 7.34 inches – a quarter wave - is as short as the antenna can be and still function. Perhaps improvements in materials, circuitry, and/or manufacturing will someday allow smaller antennae to be used in satellite tracking, but for now, a whip antenna is our only choice for robust ground to space communication.

The image at left shows an electrical wave oscillating through a full wave antenna, where the antenna is the same size as the wavelength. If the antenna were longer or shorter than the wavelength it is propagating, it would work less efficiently or not at all. A dipole antenna breaks the wave into two pieces, so it can be half as long as a full wave antenna. A quarter wave antenna - the kind used on our PTTs - breaks the wave into four pieces and can be a quarter the length.

I found the distance traveled to be quite fascinating. If you do the math, 29.38 inches (the distance it takes for our signal to complete one cycle) multiplied by 401,664,000 cycles per second equals roughly 186,000 miles per second. It takes a lot less than a second for messages to travel from the Dynamic Duo (D24 and D25) to the Argos satellite system 528 miles overhead.

Will electromagnetic radiation of an antenna hurt the eagles?

No. Terms like electromagnetic radiation are frightening, but not all electromagnetic radiation is harmful. Innately dangerous electromagnetic radiation is found in the high-frequency end of the spectrum, since high frequency waves are a lot more energetic than low frequency waves. Think of it this way: gamma rays have frequencies of 1 x 10

21 Hertz, which means that the wavelength crests, or hits its highest potential energy point, 1 sextillion times or cycles per second. That packs a punch! By contrast, visible light has a frequency of around 5 x 10

14 (500 trillion cycles per second), microwaves have a frequency of 1 x 10

10 Hertz (ten billion cycles per second), and our radio waves have a frequency of 4 x 10

6 (400 million cycles per second).

Power is also a factor. I have a 1500-watt microwave oven that can damage living tissue. However, it is literally almost 7000 times more powerful than the 225mW solar units that power the transmitter. Even cellphones produce radio waves that are more powerful and energetic than ours.

What about insect studies? Those antennae are really small!

A lot of really cool work is being done with insects. While some of the technologies involve active transmitters, which require batteries, others use passive devices like RFID tags and geolocators. Passive devices don’t require much power and can be made extremely small. A couple of links:

Unfortunately, passive devices can’t transmit. Researchers don’t get data unless the animals move in close proximity to a reader (think of a feeding station where animals might gather), or they are recaptured for a data download. Geolocators could be used to track migratory peregrine falcons that return to the same nest box year after year, but they aren’t a good fit for tracking juvenile or sub-adult eagles that wander unpredictably and often widely.

The tiny little transmitters used in tracking insects are very cool – check out that tiny backpack! – but they have short battery lives (7-21 days) and a limited tracking range on the ground only (100-500m). As neat as they are, they aren’t suitable for tracking juvenile and sub-adult eagles either.

In short…

We can’t get rid of the antenna, which is as short as it can be given the frequency of our ground to space transmission. Argos did a great job designing a package that is light, safe, reliable, and trackable almost anywhere on earth, especially given the physical requirements of the transmission system. The transmitters do not harm bald eagles or impact their social or reproductive interactions with eagles that aren’t wearing transmitters. Passive devices aren’t a good option since juvenile and sub-adult eagles range unpredictably and often widely before settling down to nest, while tiny active devices have short battery lives and a limited ground-only tracking range – something that won’t work for animals that can fly hundreds of miles and live relatively long lives.

However, research into insects and small birds is driving tracking devices to become even smaller. If at some point appropriate tracking hardware becomes available with a smaller antenna, we will use it.

Did you know?

The wavelength and frequency of electromagnetic waves are closely related. If you have a frequency, you can get the wavelength, and if you have a wavelength, you can get a frequency. With the wavelength, you can determine the length of the antenna you need to transmit or receive radio waves at a given frequency. The formula looks like this: Wavelength = Wave speed/Frequency.

Let's say that I have a frequency of 401.664 MHz, or 401,664,000 cycles per second. The wave speed is the speed of light, which can be expressed as 3x108 m/s or 300,000,000. If I divide 300,000,000 by 401,664,000, I get .7468 meters. Since I was raised in the English system, I immediately convert it to inches or feet, which gives me an antenna length of 29.38 inches. This was very helpful when trying to determine why the antennae on our PPT systems are the length they were. This web calculator provides lengths for half and quarter wave antennas if you want to play around with making them:

http://www.csgnetwork.com/antennagenericfreqlencalc.html

What could you do with an antenna? There is a community of people that listen to the earth via homemade VLF radios. This website provides an introduction to the concept and some online streams:

http://abelian.org/vlf/

Resources that helped me learn and write about this:

Since you made it to the bottom, I hope you enjoy this bonus image.

XKCD explains the spectrum as only they can!